But "Blue Rondo a la Turk," which relies on the listener hearing sets of both two and three, would get too muddy if it started to swing. "When you're swinging, you're very close to blurring the lines between duplets and triplets," London says. This can make the figure sound like a triplet (with the first two notes slurred together) instead of two eighth notes. When a piece swings, two eighth notes in succession aren't played evenly instead, the first is longer than the second. "Uneven beats are perfectly fine, but we can't do it quite as fast as with even beats." They also can't "swing" the way a lot of jazz does. For one, people's brains can't process the unusual meters as quickly as the standard ones, so they can't be performed as quickly.

"These uneven meters play by slightly different rules than the symmetrical meters," London says. "I knew that it had a visceral, toe-tapping sense of beat and rhythm," he says, "but according to most theories of rhythm and meter developed in recent decades, it couldn't, given its uneven beat structure." He says that Brubeck actually inspired much of his research into rhythm and meter. Justin London is a professor of music at Carleton College in Minnesota who specializes in music perception and cognition, particularly with respect to musical meter.

"It seemed very natural to them to be playing in this rhythm," Langham says. Within his travels he would go and hear other musicians and hear what they were doing, and he would incorporate that into his music." In the case of "Blue Rondo a la Turk," Brubeck picked up the rhythm from street musicians in Turkey. Langham says that Brubeck "was a very worldly person. Of course, novelty is in the ear of the beholder.

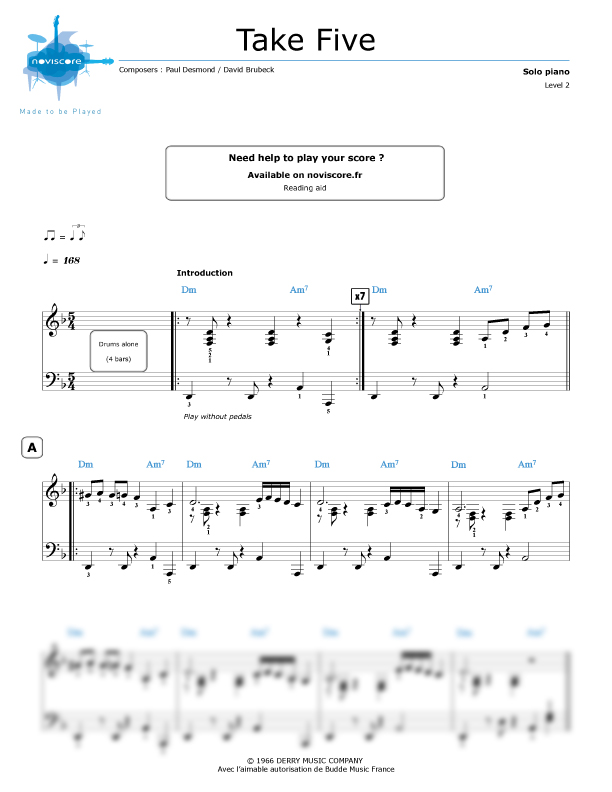

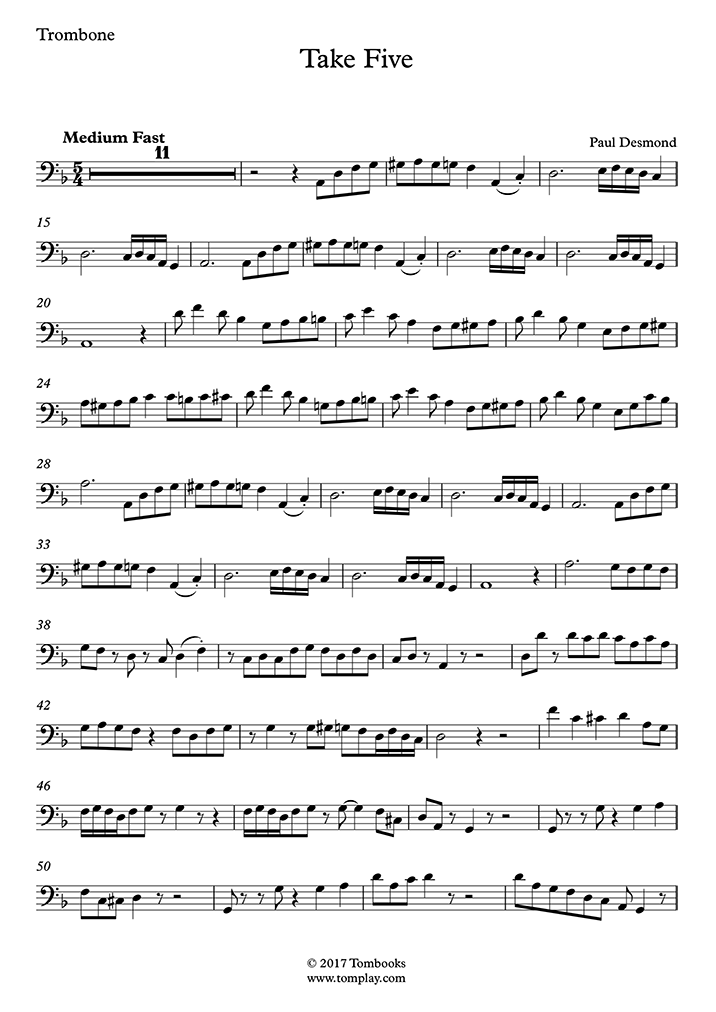

It even gets a bit more complicated: for most of the piece, there are three measures of the unusual 9/8 rhythm followed by one measure of the usual groups of three. In 9/8 time, the nine eighth notes are usually divided into three groups of three, with the stress pattern one two three one two three one two three, but "Blue Rondo" has the pattern one two one two one two one two three. "Blue Rondo a la Turk" has a time signature of 9/8. "This allowed college students to be different, in the sense of adding a funky twist to it." "Take Five," which was conceived by Brubeck's saxophonist Paul Desmond, is in 5/4 with the accent pattern one two three four five, so each measure can be thought of as being split into two uneven chunks. Langham says that from a dance point of view, the meter of "Take Five" combines a waltz and a two-step, both of which were popular in the 1950s and 1960s with the parents of teenagers. 4/4 means that there are four beats and a quarter note lasts for one beat, yielding four quarter notes in each measure.) " Take Five" and " Blue Rondo a la Turk," two of Brubeck's most popular works, are both on Time Out. (The first number, which is the top number of the time signature in sheet music, represents the number of beats in the measure, and the second number represents the note value that receives one beat. Time Out, the hit 1959 album by the Dave Brubeck Quartet, was one of the first popular jazz works to explore meters beyond the traditional 4/4 and 3/4. "He sort of tired of the traditional patterns of jazz," says Patrick Langham, a saxophonist and faculty member of the Brubeck Institute at the University of the Pacific in Stockton, Calif. The pianist and composer was an innovator, especially when it came to combining rhythms and meters in new ways. Jazz legend Dave Brubeck died December 5, just one day before his 92nd birthday.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)